Overview

The kidneys perform many jobs but only water and acid-base balance are topics of this tutorial. The goal is to present a way to understand rather than memorize. The details are many but presented in small bites ... though it won't feel like it at first ... but will lead to an amazing understanding of kidney function.

When completed, you will understand how the flow of 'future urine' ... the filtrate ... provides solutes that will draw water back into the blood. You'll find that the rate of that flow is vital and how it is controlled. How does the kidney 'know' if it's too fast or slow and how does it fix it?

What are the details behind the production of filtrate from plasma? And if blood pressure is too high will it 'blow a hole' in the nephrons? And, going down the length of the tubule, what is the job of each section? How does the tubule identify which components of the filtrate should be reabsorbed and which ignored? And why do certain ones need to be reabsorbed in the first place?

It's a long story but adventurous and thought provoking. I hope you enjoy learning.

Excretory System

Interactions & Insights

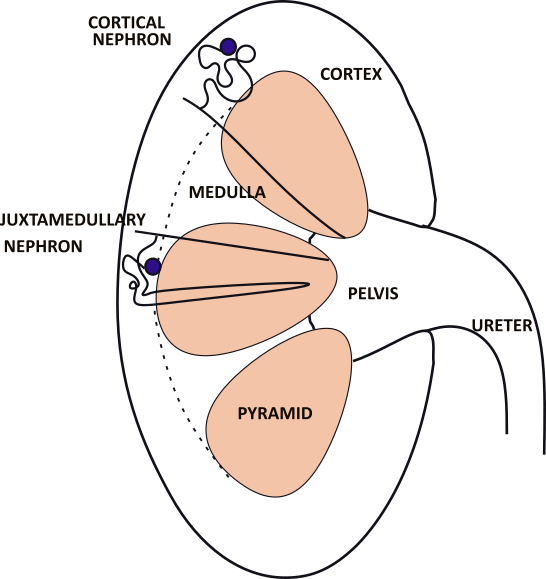

The adult kidney is ~4.5 inches long. The funnel shaped ureter exiting the kidney drains 5-10 milliliters of urine from the pelvis of the kidney. The solid tissue of the kidney consists of 8-10 pyramids, each shaped like a kernel of corn. Between them are the columns where nerves and blood vessels are located.

Small outlines of the two types of nephrons are shown in the kidney. A cortical nephron is drawn in the top pyramid and a juxtamedullary nephron in the center pyramid.

Nephrons

Cortical Nephron

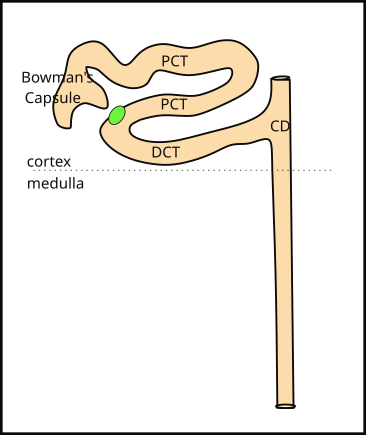

Cortical nephrons are so named because their Bowman's capsule is located in the 1 inch deep cortex. They comprise 85% of all nephrons. The hollow Bowman's capsule is indented where the glomerulus, a tuft of capillaries, fits (not shown).

The capsule fills with filtered blood plasma ... filtrate ... that flows down the tubule. The tubule is convoluted and intertwines around itself; it is divided into a proximal (PCT) and distal (DCT) section. The dividing line between these two sections is a specialized group of tubule cells; it is shown as a green oval in the illustration.

The distal convoluted tubule (DCT) is about 1/3rd the length of the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT). It empties its filtrate into the collecting duct (CD). Many separate nephrons empty into these ducts and the ducts converge several times before finally emptying their contents into the renal pelvis.

Juxtamedullary Nephron

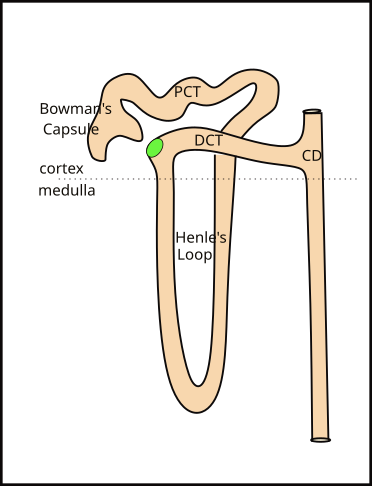

Juxtamedullary nephrons are so named because their Bowman's capsule is close to (juxta...) the beginning of the medulla. Look at the kidney illustration to compare the locations of the capsule of each type of nephron. The only difference between the two types is that the juxtamedullary nephron has a long loop (Loop of Henle) extending toward the center of the kidney. The loop begins as a continuation of the PCT and ends where it becomes the DCT.

There are approximately one million nephrons in each kidney. Only ~15% of these are juxtamedullary. Their Henle's loops are bundled together into from 8-10 groups called pyramids. Collecting ducts receive filtrate from both types of nephrons. At the tip of each pyramid are approximately 30 collecting duct openings that deliver the final product, urine, to the renal pelvis.

***************************

Relationships

Cause-and-Effect Relationships

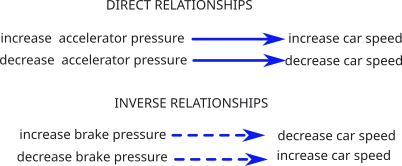

Understanding how something happens is much more useful than simply knowing that it 'does' happen. It goes far beyond memorizing the correct response to a physiological question. These simple examples are meant to insure the reader understands the meaning of the arrow symbolism employed throughout this tutorial.

A direct relationship is when a change in the 'cause' results in a similar change in the 'effect'. For example: Increasing pressure on the accelerator increases the speed of the car. The reverse is also true. Throughout the tutorial, direct relationships are indicated by a solid blue arrow.

An inverse relationship is when a change in the 'cause' results in an opposite change in the 'effect." For example: Increasing the pressure on the brake decreases the speed of the car; and vice versa. These relationships are indicated by a dashed blue arrow.

***************************

Membrane Potentials

Transporters and channels are produced by the Golgi Apparatus. They are embedded in membranous sections of the Apparatus that are pinched off and form into vesicles. The vesicles can be 'trafficked' to the cell surface where exocytosis makes them part of the cell membrane. Vesicles can also be 'stored' by endocytosis.

The activities of membrane-embedded ion transporters and channels can establish an uneven distribution of charges along the inner and outer surfaces of membranes. They are measured by a voltmeter that calibrates the charge at the outer surface to zero then records the charge at the inner surface. The 'membrane potential' is the inner charge in millivolts (mV), unless specifically stated it refers to the outer surface.

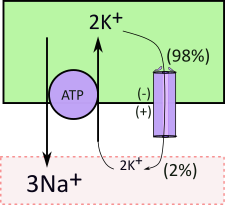

The sodium-potassium pump (purple circle) and associated channel exemplifies how this works. The sodium-potassium transporter is referred to as a 'pump' because it uses the energy of ATP that enables ion transport even against a concentration gradient. It moves 3Na+ out of cells in exchange for 2K+. Note that the potassium is moved against its concentration gradient (2:98). This electrically-uneven exchange leaves the inner surface with a net loss of one positive charge that is expressed as a negative voltage. Of course the outer surface has the same charge difference but it is positive.

The membrane potential affects ion diffusion through any channels that specifically allows passage of that ion. Diffusion occurs due to a concentration gradient (98:2) ... in this example the movement is outward. But diffusion is also affected by charge differences (membrane potential) ... in this case the negative inner and positive outer potentials tend to inhibit the diffusion. When transporters create membrane potentials the diffusion, through channels, is along an 'electrochemical gradient'.

Some channels are 'wide open' while others permit only minimal diffusion. In this example the channel is the minimal variety. In conjunction with the pump, it is responsible for the huge difference (98:2) in inner and outer potassium concentrations.

***************************

Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

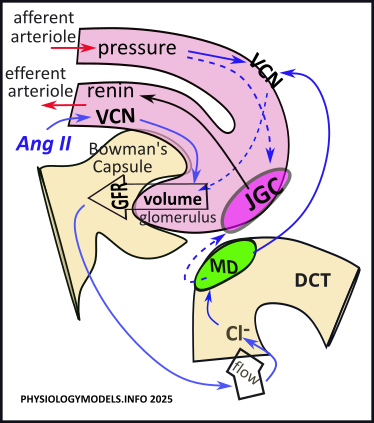

The illustration shows details of what occurs at the beginning of the nephron. An afferent arteriole delivers blood to each nephron. It branches into a net of capillaries called the glomerulus that is embedded in an indentation in Bowman's capsule. After filtration, the remaining blood leaves the glomerulus via the efferent arteriole. At the lower right is a section of the same tubule; it shows the beginning of the distal convoluted tubule (DCT). The 'flow arrow' indicates the direction of filtrate movement. The green oval represents a group of specialized cells called the macula densa (MD).

The rate of blood flow through the afferent arterial is ~1000mL/min; of this ~60% is plasma. Therefore, ~600mL/min of plasma enters the glomerulus; 1/5th of this becomes filtrate. This yields a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of ~120ml/min/kidney.

The force that 'pushes' the plasma into the capsule is hydrostatic pressure, not 'blood pressure'. Hydrostatic pressure is due to gravity acting on the volume and density of the fluid. In the glomerulus it is only ~10mmHg. Any change in the glomerular volume will affect the GFR.

Amazingly, the volume in the glomerulus is kept essentially constant when the mean arterial blood pressure ranges between 60-160mmHg. If this were not the case, fluctuations in glomerular volume would become too low to produce any filtrate or too high and rupture the nephrons.

Short-term maintenance of ~10mmHg of pressure in the glomerulus is controlled locally by a pair of side-by-side specialized cells where the afferent arteriole and tubule contact each other. The region is called the juxtaglomerular apparatus. The special region in the wall of the tubule is the macula densa (green oval); the adjacent region in the wall of the afferent arteriole is the juxtaglomerular cells (pink oval).

Myogenic Response

"Myo-" refers to muscle and "-genic" refers the origin. The 'myogenic response' is a response that originates in vascular smooth muscle. In the afferent arterioles leading to glomeruli, an increase in blood pressure causes increased constriction

( )

of the arteriole, and increased VCN reduces the volume (

)

of the arteriole, and increased VCN reduces the volume ( ) delivered to the glomeruli . The reverse would is also true.

) delivered to the glomeruli . The reverse would is also true.

Tubuloglomerular Feedback

The tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism evaluates the outcome of the myogenic response. If blood pressure is too high diuretics will need to be administered. If blood pressure is too low, the tubuloglomerular feedback modifies the VCN and initiates response that will ultimately lead to an increase in blood pressure.

The GFR drives filtrate flow through the nephron. Along the way, various transporters retrieve certain solutes and secrete others; the solute composition of the filtrate is altered as it heads toward becoming urine. On passing into the DCT, the macula densa uptakes chloride from the filtrate; it uses this to inhibit the activity of the adjacent JGC. The result is that this second group of cells, lining the afferent arteriole, retains renin that it has produced.

If filtrate flow is too slow, insufficient chloride delivery inhibits ( ) the release of calcium by the MD. This lack of inhibition permits (

) the release of calcium by the MD. This lack of inhibition permits ( ) the JGC to release (

) the JGC to release ( ) renin into the bloodstream.

) renin into the bloodstream.

The steps in this series are as follows:

- Low GFR causes slow filtrate flow.

- Slow flow reduces chloride delivery to the MD.

- The macula densa stops releasing calcium to the JGC.

- The JGC releases renin.

***************************

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone-System (RAAS)

Hormonal Control

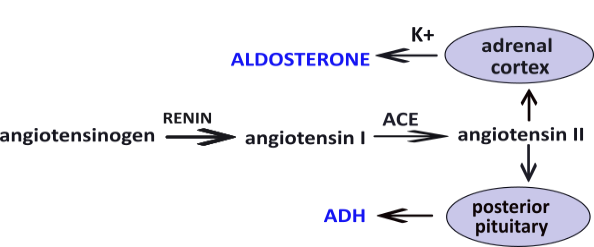

The enzyme renin converts the pre-hormone angiotensinogen into angiotensin I ... another pre-hormone. A second enzyme, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) converts angiotensin I into angiotensin II. This hormone stimulates (1) the posterior pituitary to secrete antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and, (2) the adrenal cortex to secrete aldosterone. Independent of water balance, hyperkalemia, high blood potassium (K+), also stimulates aldosterone secretion.

Both aldosterone and ADH are released at base-line levels regardless of blood pressure. Hypovolemia (low blood volume) causes the RAAS response but, as noted, hyperkalemia (high blood potassium) causes release of aldosterone independent of blood pressure. Also, ADH is independently released if solute concentration in the blood is too high.

The increased concentrations of these hormones is short-lived. Renin is inactivated after 10-15 minutes. Angiotensin II is inactive after 30 seconds while circulating and is degraded within 15-30 minutes in tissues. Aldosterone is cleared by the kidneys and liver in 20 minutes. ADH is cleared in 10-20 minutes.

Angiotensin II, aldosterone and ADH appear in illustrations throughout this tutorial. They will be in blue text for easy recognition. Their functions are described in the Regulation sections at the end of each description.

Regulation

Angiotensin II (Ang II) increases vasoconstriction (VCN) in the efferent arteriole. This reduces the ease of flow out of the glomerulus thus increasing glomerular volume during low blood pressure and reduced GFR.

***************************

Illustrations

... and How to Interpret Them

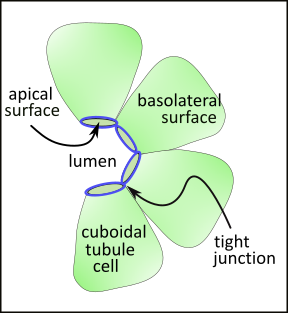

This partial cross-section of a tubule shows a single layer of cubodial cells. The surface of these cells facing the lumen is smaller than the sides (lateral) or outer (basal) surfaces. Accordingly, the shape of these cells resembles a pyramid with a flattened apex. The term 'apical' refers to the smaller portion of the cell membrane facing the tubular lumen. The sides and outermost surfaces are referred to as basolateral.

The apical and basolateral surfaces have different membrane-embedded transporters and channels. These are kept apart from each other due to tight junctions (blue circles) that separate these surfaces. In general, these junctions prevent indiscriminant leakage of filtrate from the tubule. However, regionally, there are often small 'pores' that do allow water and/or specific ions to diffuse out.

***************************

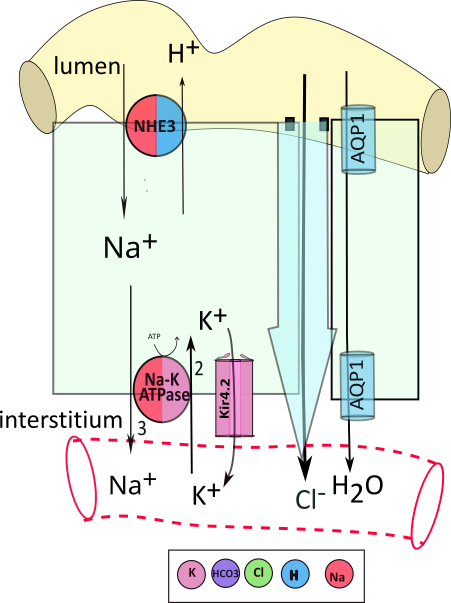

The illustrations throughout this tutorial resemble the one presented here. Each illustration will show a yellow section of the nephron tubule. A light green rectangle ... pardon the shape ... represents a tubule cell. Below the cell is a clear area ... the interstitium ... with a capillary running through it. This illustration shows part of a second cell with a small space next to the large cell. The large blue arrow between the two represents water diffusing from the tubule to the interstitium then the blood. Channels are embedded in the small cell showing that water (H2O) can also diffuse through them into the blood.

Black arrows show the movement of solutes from one region to the next; the item being moved is shown at its destination. A circles is a representative transporters embedded in the cell membrane. In this example, an apical transporter moves sodium (Na+) from the filtrate into the cell in exchange for hydrogen (H+). Arrows are beside the transporter against the color associated with the solute being moved. The key below the illustration indicates Na+ movement is red and hydrogen movement is blue.

Cells have sodium-potassium pumps (Na-K-ATPase) in the basolateral membrane. They use the energy of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to exchange 3 sodium (Na+) for 2 potassium (K+) across the membrane. These pumps are ubiquitous, found everywhere, and always on the basolateral border. They are accompanied by channels that permit a small recycling of potassium back to the interstitium to insure continued operation of the pump and the establishment of a membrane potential.

Adjacent tubule cells are separated by a space filled with interstitial fluid; this region is referred to as paracellular (adjacent to cells) to distinguish movement through it as distinct from movement through the cytoplasm (transcellular); it is illustrated between the large cell and a portion of another cell with a large blue arrow between them.

As described earlier, all tubule cells are attached to their neighbors at their apical surfaces by a tight junction containing claudin proteins (small black squares) that form pores for the diffusion of specific solutes. In this example, chloride passes through these small pores into the interstitial space. The paracellular diffusion of water (large blue arrow) is called bulk flow and the transportation of solutes within it is referred to as solvent drag.

***************************

The remainder of the tutorial is centered on visualization of cellular activities. The illustrations employ information reviewed above and how activities are interrelated. In some sections, certain structures will be blurred out; however, those that directly pertain to the description will be clearly shown.

Although transporters and channels are described as if there is only one be aware that they are actually numerous throughout the cell. And, arrows are numerous. The attempt is to show how the product of one action becomes the reactant of another ... though this can not always be drawn and the reader must 'follow the path' without the assistance of an arrow.

Terminology:

- Uptake...can refer to movement into the cell from either the filtrate or the interstitium.

- Efflux...can refer to movement out of the cell into the filtrate or the interstitium.

- Secretion...refers to movement from the cell to the filtrate.

- Excretion...refers to movement from the body.

- Reabsorption...refers to movement to the interstitium.

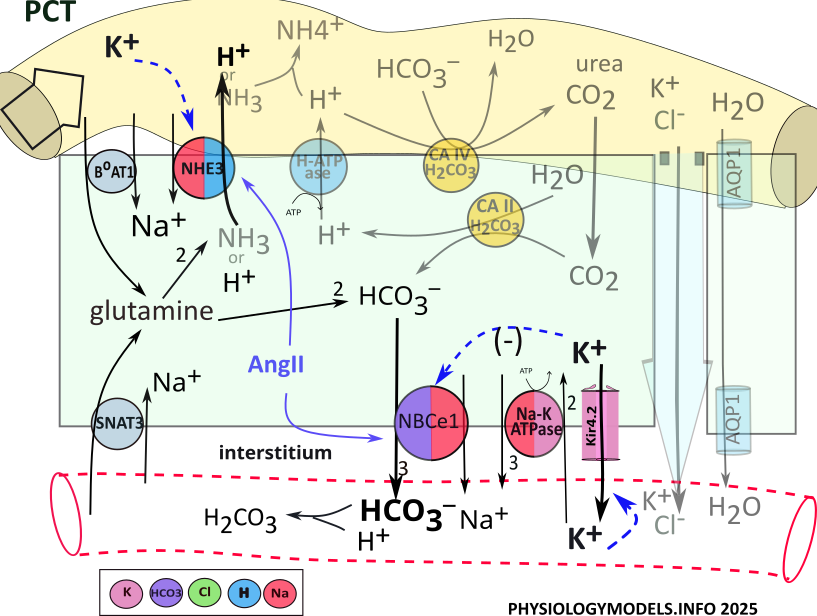

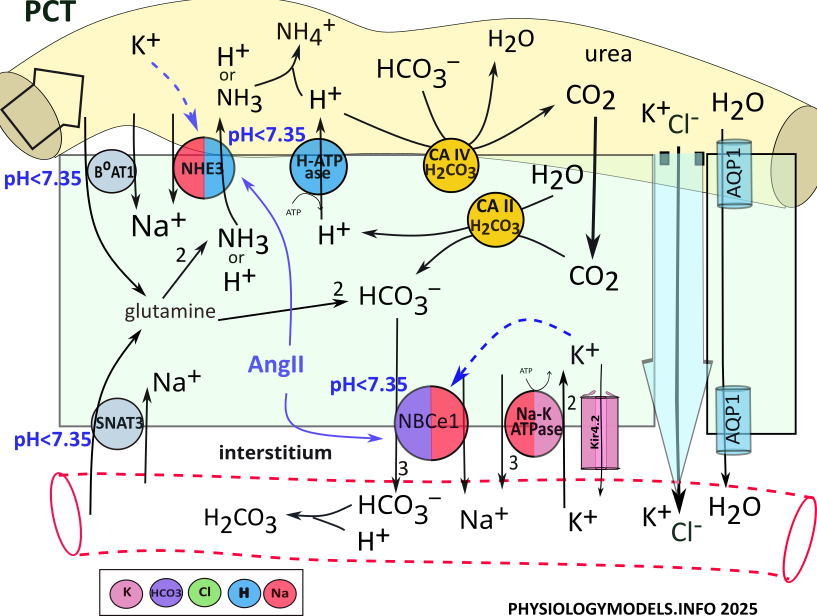

PCT Water Balance

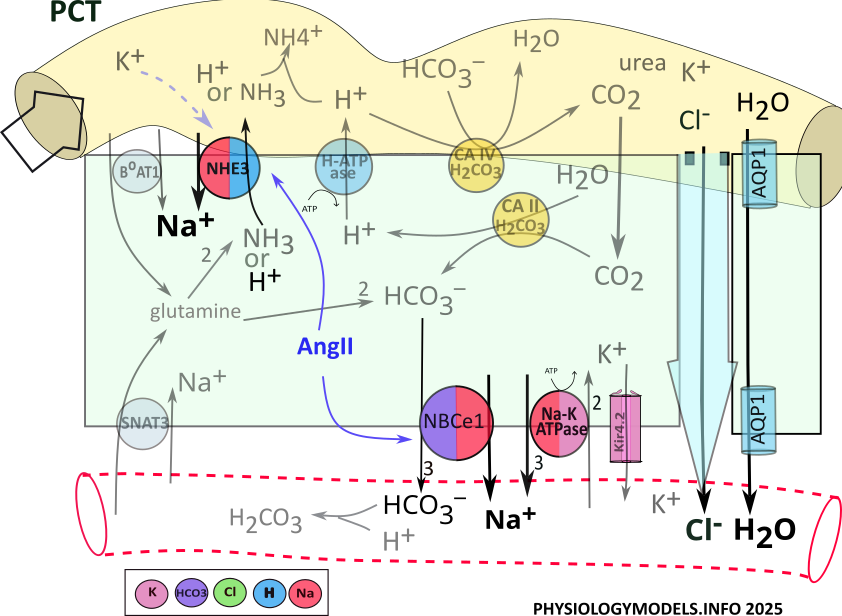

Approximately 2/3rds of filtered sodium, chloride and water are reabsorbed in the PCT.

Before water can be reabsorbed, solutes must be moved out of the filtrate into the interstitium producing an osmotic concentration. Only then can water diffuse (osmosis) into that region. Such a region used to be referred to as having high osmolarity, but that term is now out of favor.

Sodium and chloride are the primary solutes transported from the filtrate to the interstitium surrounding the tubules. In the PCT, the apical NHE3 transporter uptakes sodium from the filtrate in exchange for cellular hydrogen.

Point of information: The name of a transporter often reflects what is being moved. For example, NBCe1 stands for sodium (N) bicarbonate (B) cotransporter (C) that is electrogenic (e). It is electrogenic because it establishes a membrane potential. The images are color coded; a key is provided by each illustration.

Sodium enters the cell via NHE3 activity in exchange for the secretion of hydrogen. Sodium is moved to the interstitium, along with three bicarbonate ions, by NBCe1. Sodium is also reabsorbed by the sodium-potassium pump.

Chloride accompanies the reabsorption of sodium by transcellular and paracellular pathways. It diffuses through aquaporin channels located in the apical and the basolateral borders. It also travels between the cells, by solvent drag, within the bulk flow of water.

The sequence of events increasing the osmotic concentation and water reabsorption is:

- NHE3 moves sodium from the filtrate in exchange for hydrogen.

- NBCe1 and Na-K-ATPase complete sodium reabsorption into the interstitium.

- Chloride moves via solvent drag within the bulk flow of water.

- Water diffuses through AQP1 channels.

Regulation

During hypovolemia, angiotensin II stimulates ( ) both NHE3 and NBCe1 that increases osmotic concentration and water reabsorption. This upregulation continues until hypovolemia has been reduced, blood pressure increases, renin is no longer released, and angiotensin II is inactivated.

) both NHE3 and NBCe1 that increases osmotic concentration and water reabsorption. This upregulation continues until hypovolemia has been reduced, blood pressure increases, renin is no longer released, and angiotensin II is inactivated.

***************************

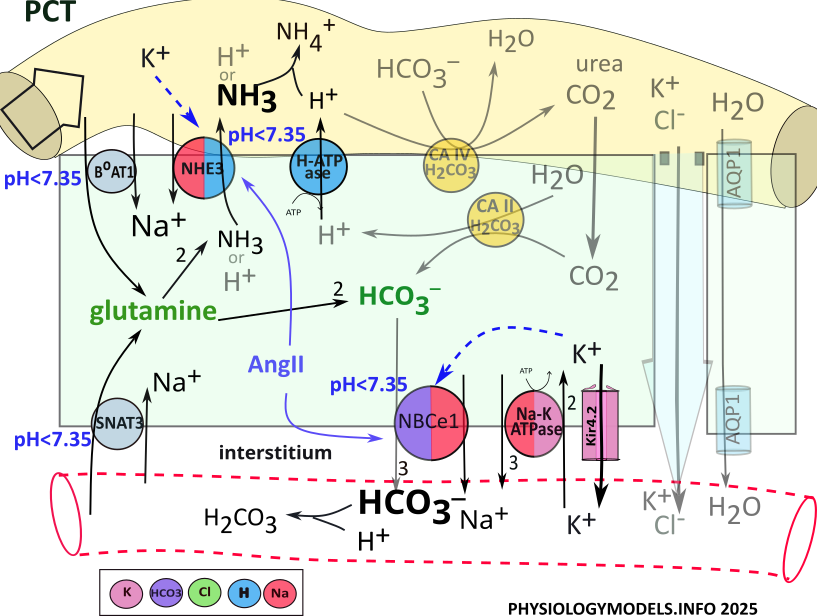

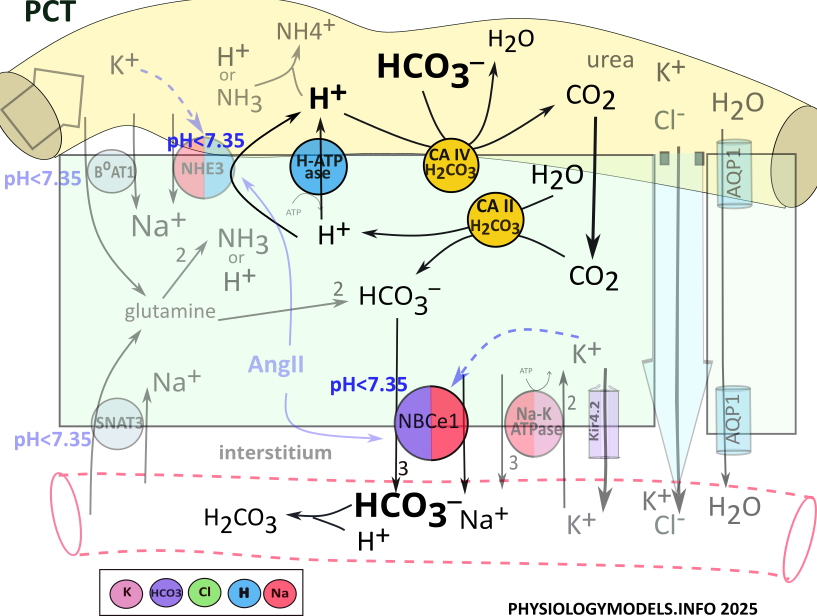

PCT Acid-Base Balance

Normal pH ranges from 7.35 to 7.45. Acidosis is a pH less than 7.35 while alkalosis is greater than 7.45. The nephron can mitigate (reduce) acidosis by secreting hydrogen and/or reabsorbing bicarbonate. The opposite is the case during alkalosis ... hydrogen is reabsorbed and/or bicarbonate is secreted.

The illustration indicates that three apical transporters and one basolateral transporter are stimulated by acidosis. Within the cell, glutamine and bicarbonate...emphasized by green color...play central roles in the following descriptions.

Ammoniagenesis

The 'origin of ammonia' begins when the amino acid glutamine is transported into PCT cells from the filtrate and the blood. It is metabolized by cytoplasmic enzymes (not shown) to produce two ammonia molecules and two bicarbonate ions. Each ammonia is secreted to the filtrate by NHE3 and three bicarbonates are reabsorbed by NBCe1.

During acidosis, NHE3 secretes ammonia in place of hydrogen. However, hydrogen secretion by H-ATPase is upregulated to play this role during acidosis. In the filtrate, hydrogen and ammonia combine forming ammonium. In the bloodstream, bicarbonate buffers hydrogen forming carbonic acid.

The sequence of events during ammoniagenesis is:

- BoAT and SNAT3 transport glutamine into the cell.

- Ammoniagenesis enzymes convert glutamine to 2 NH3 and 2 HCO3-.

- NHE3 exchanges NH3 for Na+.

- NBCe1 cotransports 3 HCO3- and Na+ to the blood.

- Bicarbonate buffers hydrogen in the blood producing carbonic acid.

- Ammonia buffers hydrogen in the filtrate producing ammonium.

Carbonic Anhydrase

Point of interest: Carbon dioxide, produced during metabolism, is taken into red blood cells where it is converted to bicarbonate then released into the plasma. Within the normal pH range of 7.35-7.45, the equilibrium ratio between bicarbonate and carbonic acid is 20:1.

Eventhough bicarbonate is not a perfect buffer...as indicated by the ratio above...its loss would be a waste. This potential problem is exacerbated by the fact that there are no transporters or channels to retrieve bicarbonate from the filtrate. However, the nephron has a really neat routine that solves this problem.

The 'conductor' in orchestrating this routine is the enzyme carbonic anhydrase. This enzyme catalyzes the following reversible reactions:

H2CO3

H2CO3  H2O + CO2

H2O + CO2

Bicarbonate Reabsorption

Carbonic anhydrase (CA IV) is attached to the apical border of PCT cells where it binds with filtrate bicarbonate; hydrogen is secreted from the cell to complete the required input for the enzyme. Carbonic anhydrase combines them into carbonic acid that it decomposes and releases as water and carbon dioxide.

Once in the cell, the diffusable carbon dioxide encounters cytoplasmic carbonic anhydrase (CA II) the catalyzes the reaction in reverse. It converts carbon dioxide and water into carbonic acid that is released as hydrogen and bicarbonate. H-ATPase recycles hydrogen to the filtrate to be 'reused' by CAIV, while the bicarbonate is reabsorbed.

The sequence of events that reabsorbs filtrate bicarbonate is:

- H-ATPase secretes H+ into the lumen.

- Apical carbonic anhydrase (CA IV) combines hydrogen and bicarbonate to form carbonic acid that it releases as water and carbon dioxide.

- CO2 diffuses into the cytoplasm.

- Cytoplasmic CA II recombines carbon dioxide and water to reform carbonic acid that it releases as hydrogen and bicarbonate.

- Hydrogen is secreted into the lumen by H-ATPase.

- Bicarbonate is reabsorbed into the interstitium by NBCe1.

- Bicarbonate buffers extracellular hydrogen mitigating acidosis.

Regulation

Once sufficient loss of hydrogen plus the retention of bicarbonate have mitigated the pH back into the normal range, ammoniagenesis will stop.

...and the Effect of Hypokalemia (Alkalosis)

Hypokalemia is associated with alkalosis; this is observed in several segments along the nephron. It affects transporters in various ways such that hydrogen secretion and/or bicarbonate reabsorption are increased. Both lead to alkalosis.

Low filtrate potassium stimulates apical NHE3 to increase hydrogen secretion ( ). The loss of hydrogen favors a change toward alkalosis.

). The loss of hydrogen favors a change toward alkalosis.

At the basolateral membrane, low potassium increases potassium efflux ( ). The decreased cellular potassium hyperpolarizes (more negative) the membrane potential that stimulates voltage-sensitive NBCe1 (

). The decreased cellular potassium hyperpolarizes (more negative) the membrane potential that stimulates voltage-sensitive NBCe1 ( ). Increased bicarbonate reabsorption buffers hydrogen favoring a change toward alkalosis.

). Increased bicarbonate reabsorption buffers hydrogen favoring a change toward alkalosis.

***************************

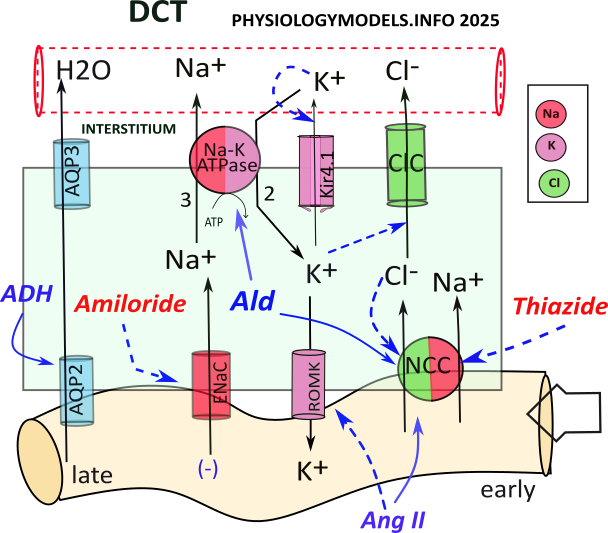

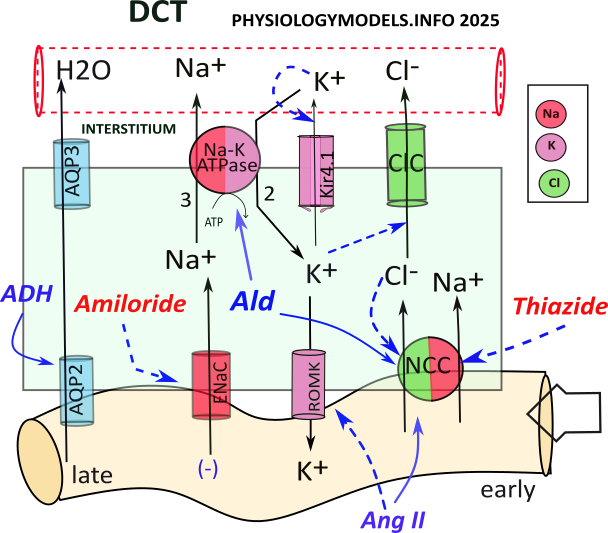

DCT Activities & Aldosterone Paradox

The role of the DCT is sodium chloride and water reabsorption and potassium balance.

During hypovolemia, 8-10% of filtered water can be reabsorbed due to DCT activities. Though short in length, the DCT handles sodium transport differently in its early and late segments. Solutes are transported to the same peritubular capillaries that intertwine with both convoluted tubules.

NCC cotransports sodium and chloride from the filtrate; sodium is reabsorbed by the sodium-potassium pump and chloride diffuses to the interstitium though ClC channels.

Sodium, that diffuses through the ENaC channel, is driven by two forces: (1) the amount of filtrate sodium it receives, and (2) the sodium concentration gradient. The gradient is estalished by sodium-potassium pump activity.

Importantly, the sodium uptake creates a lumen-negative potential. This negativity along the outer basolateral border facilitates the diffusion of positive potassium back into the filtrate. This is the source of 'potassium wasting.'

The sequence of events is as follows:

- NCC cotransports sodium and chloride into the cell.

- Sodium is transported to the intersitium by the sodium-potassium pump.

- Chloride diffuses to the interstitium through ClC channels.

- ENaC permits diffusion of sodium into the cell.

- A lumen-negative potential is created.

- Potassium diffuses to the filtrate through ROMK channels.

Hyperkalemia

The normal potassium concentration gradient is 98% intracellular vs. 2% extracellular. The diffusion of potassium from the cell is potentially very high but depends on the channels available. At the basolateral border, Kir channels allow only minimal diffusion. At the apical border, 'wide open' ROMK channels are found.

Hyperkalemia (high blood potassium) reduces the 98:2 concentration gradient so that less diffuses into the interstitium. The overall effect is to 'shunt' potassium to the filtrate so blood levels can be lowered.

While in the cytoplasm, potassium, in a roundabout way, inhibits NCC transporters and diffusion through channels. Follow the blue relationship arrows through the following sequence of events:

- Hyperkalemia reduces potassium diffusion from the cell.

- Higher cytoplasmic potassium reduces chloride loss through ClC.

- Increased cytoplasmic chloride inhibits NCC.

- Reduced NCC activity reduces sodium uptake from the filtrate.

- More filtrate sodium is delivered to ENaC.

- Lumen-negative potential is increased allowing increased potassium diffusion via ROMK...potassium is 'wasted'.

Aldosterone Paradox

The paradox (apparent contradiction) is ...how can hyperkalemia sometime cause potassium wasting without water reabsorption, while at other times, cause water reabsorption without potassium wasting?

The previous section describes hyperkalemia causing potassium wasting; water reabsorption is mainly governed by NCC which was inhibited. However, hyperkalemia during hypovolemia causes the opposite.

Aldosterone stimulates ( ) two transporters: the sodium-potassium pump and NCC. Stimulaltion of the pump facilitates sodium, and chloride, reabsorption...and ADH inserts aquaporins allowing osmosis from this segment. The aldosterone stimulation of NCC, greater than its inhibition by hyperkalemia, leaves less filtrate sodium for ENaC channels...therefore less potassium wasting.

) two transporters: the sodium-potassium pump and NCC. Stimulaltion of the pump facilitates sodium, and chloride, reabsorption...and ADH inserts aquaporins allowing osmosis from this segment. The aldosterone stimulation of NCC, greater than its inhibition by hyperkalemia, leaves less filtrate sodium for ENaC channels...therefore less potassium wasting.

Angiotensin II , also present during hypovolemia, stimulates ( ) NCC while inhibiting (

) NCC while inhibiting ( ) ROMK. Increased NCC activity ultimately increases water reabsorption and inhibition of ROMK reduces potassium secretion lowering potassium loss.

) ROMK. Increased NCC activity ultimately increases water reabsorption and inhibition of ROMK reduces potassium secretion lowering potassium loss.

So, the answer to the paradox is that the nephron favors correcting negative water balance over correcting excess potassium.

***************************

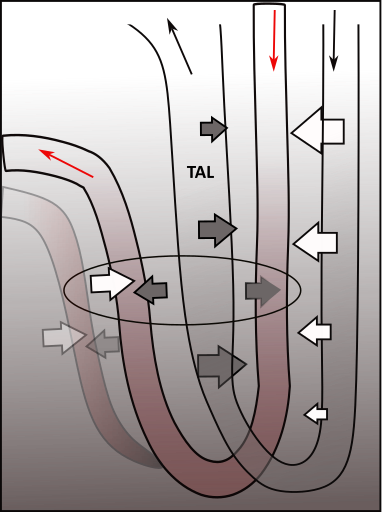

Countercurrents

In Juxtamedullary nephrons, filtrate leaving the PCT enters Henle's loop. Here, the osmotic concentration that will enable water reabsorption is established.

The illustration shows Henle's loop and the vasa recta suspended in the osmotic concentration gradient in a renal pyramid. The following description explains how the gradient is created and maintained and how solutes and water are returned to the blood.

The shaded background of the illustration indicates the concentration of solutes; they are most concentrated at the bottom. Suspended within this are two loops; Henle's loop (clear) and the vasa recta (red). Arrows at the top indicate the direction of filtrate and blood flow.

At the far right are four white arrows exiting the descending limb of Henle; they represent osmosis. There is a single white arrow showing water entering the ascending vasa recta.

The grey arrows indicate solute movements. Three are leaving the thick ascending limb (TAL) of Henle; each limb of the vasa recta receives a grey arrow. There is more than one ascending vasa recta per loop as indicated in the background.

Countercurrent Multiplier

In order for water to be reabsorbed there must be an osmotic concentration region. Solutes are moved to this region by TAL. This is represented by three grey arrows pointing outward from TAL. The most solute leaves TAL at the bend and decreases as the filtrate moves upward. This is indicated by the relative sizes of the three grey arrows.

Water diffuses from the filtrate as it flows down the thin descending limb of Henle. The progressively decreasing size of the white arrows indicates that the greatest water loss occurs initially. Because of this water loss, the filtrate solute concentration is greatest at the bend.

As the filtrate ascends through the thick ascending limb (TAL) it transports these solutes back out into the interstitium. The most is transported near the bend because that is where the solutes are most concentrated. As the filtrate ascends the solutes become fewer and their movement into the interstitium is less. These differences are represented by the progressively decreasing size of the grey arrows.

The interplay between Henle's two limbs establishes and maintains the gradient in the medullary interstitium.

Countercurrent Exchanger

The oval in the illustration indicates water and solute movements occurring in the vasa recta. There are usually multiple ascending limbs as represented by the blurred one.

The descending vasa recta is only permeable to solutes (grey arrow). As the blood descends, more solutes diffuses into it ... because more are available. But, after turning the bend, the capillary also becomes permeable to water (paired grey and white arrows). Branching of the ascending capillary slows the blood flow to give more time for better equilibration of solutes and water with the interstitium. This 'exchange' ... solute for water ... is the origin of the name of this mechanism.

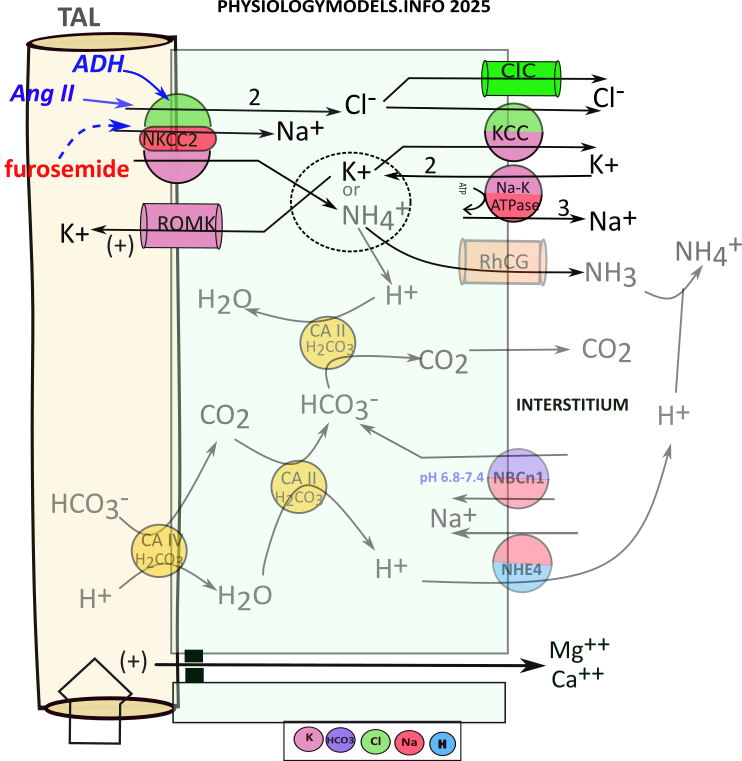

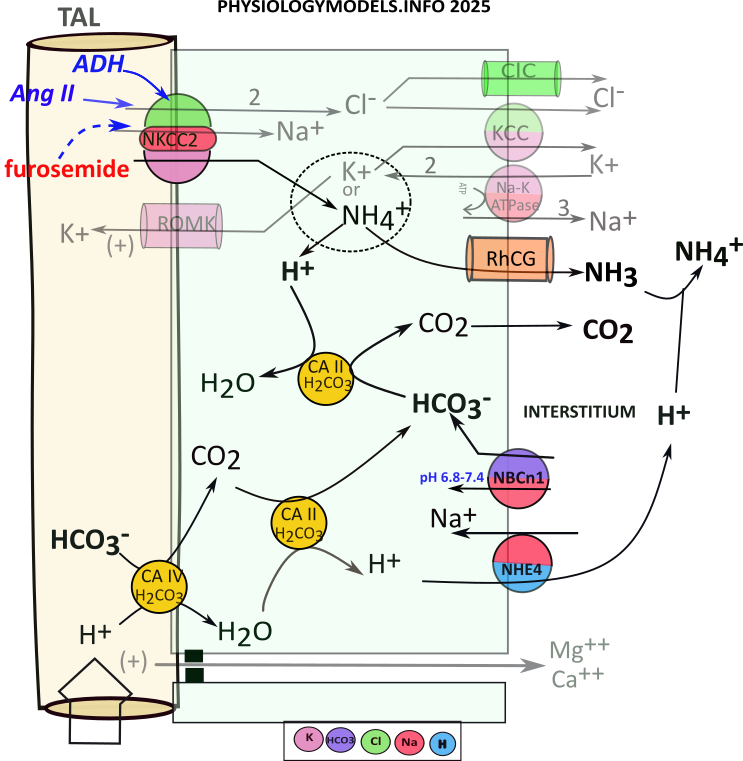

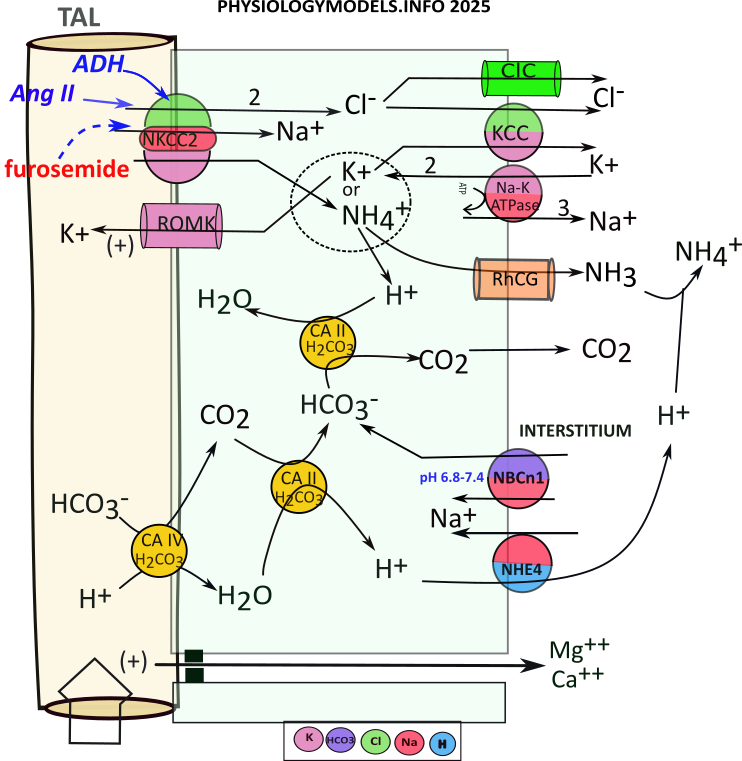

TAL Water Balance

The apical NKCC2 transporter ... unique to this section ... does most of the work by cotransporting sodium, two chlorides and potassium into the cell ... an electroneutral maneuver. Potassium is recycled to the filtrate to insure the continued operation of NKCC2. This electrogenic maneuver creats a lumen-positive potential (+) that "pushes" cations between these cells. The tight junctions in the TAL do not permit osmosis.

At the basolateral side of the cell, the sodium-potassium pump operates as usual. The ions imported by NKCC2 are moved to the interstitium by this pump, a channel, and a 'content-driven' cotransporter.

The sequence of events that contributes to the medullary osmotic gradient is as follows:

- NKCC2 moves 1 sodium, 1 potassium, and 2 chlorides .

- Sodium reabsorption is completed by the sodium-potassium pump.

- Chloride diffuses to the interstitium via ClC channels.

- Chloride and potassium enter the interstitium via KCC.

- The basolateral sodium-potassium pump exchanges sodium for potassium.

- Apical ROMK channels allow potassium to diffuse back into the filtrate.

- This increased potassium secretion produces a lumen-positive potential.

- Lumen-positive potential facilitates cation diffusion between cells.

Regulation

During hypovolemia, ADH and angiotensin II stimulate ( ) NKCC2 that increases the osmotic concentration throughout the gradient. This will facilitate increased osmosis from the descending limb of Henle as well as its reabsorption in the vasa recta.

) NKCC2 that increases the osmotic concentration throughout the gradient. This will facilitate increased osmosis from the descending limb of Henle as well as its reabsorption in the vasa recta.

***************************

TAL Ammonium Reabsorption

Recall that carbonic anhydrase catalyzes the following reversible reaction:

During acidosis, the filtrate reaching TAL will have high a ammonium concentration due to ammoniagenesis in the PCT. NKCC2 will uptake sodium, potassium (or ammonium) and two chlorides. Cytoplasmic bicarbonate will 'extract' a hydrogen from ammonium leaving behind ammonia that diffuses to the interstitium. For this to continue there must be a constant supply of bicarbonate.

There is little bicarbonate remaining in the filtrate as a result of ammoniagenesis. Nonetheless, apical carbonic anhydrase (CAIV) converts what is available to carbon dioxide that diffuses into the cell. There, it binds with CAII that converts it to bicarbonate and hydrogen. This hydrogen is transported to the interstitium.

The ammonium uptake provides a continual supply of hydrogen but filtrate bicarbonate is a limiting factor in 'driving' its influx. However, an 'emergency' bicarbonate source is derived from NBCn1 transporting interstitial bicarbonate directly into the cell.

Regardless of bicarbonate source, the ammonia diffuses to the interstitium as does carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide is picked up by capillaries and red blood cells convert it to bicarbonate. The ammonia and ammonium in the interstitium contribute 10-15% of the osmotic concentration.

The sequence of events is as follows:

- NKCC2 uptakes ammonium that ionizes to ammonia and hydrogen:

- ...Ammonia diffuses to interstitium through RhCG channels.

- ...Hydrogen combines with bicarbonate via CAII activity that releases carbon dioxide.

- Carbon dioxide diffuses to the interstitium.

- Bicarbonate is continually supplied by:

- ...the filtate via CAIV & CAII with hydrogen moved to the interstitium via NHE4.

- ...from the interstitium via NBCn1.

***************************

Collecting Duct

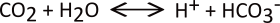

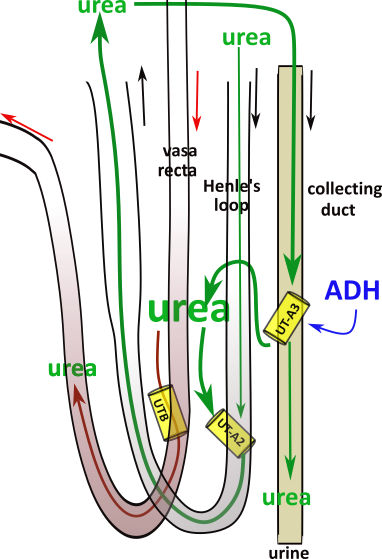

The illustration shows a juxtamedullary nephron connecting to a single collecting duct. In reality, there are many ducts, merging together, that eventually open at the tip of the pyramid. There are roughly 30 duct openings per pyramid and there are 8-10 pyramids per kidney. And only 15% of the million or so nephrons are of this type ... still a lot in one small region.

All nephrons connect with the collecting ducts. Each begins as a cortical collecting duct (CCD) and receives input from numerous cortical nephrons. As it descends into the medulla, juxtamedullary nephrons connect to it. Continuing, it is referred to as the outer medullary collecting duct (OMCD) and the remaining part is the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD).

There are three cell types comprising the tubule walls; principal cells, intercalated A cells and intercalated B cells. Intercalated means 'inserted among'. Principal cells are involved with water balance and potassium excretion. The IC-A cells are most active in during acidosis and IC-B are most active during alkalosis.

Principal cells are present in all sections of the duct; intercalated cells are most abundant in the CCD and OMCD with few in the IMCD.

***************************

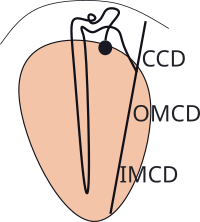

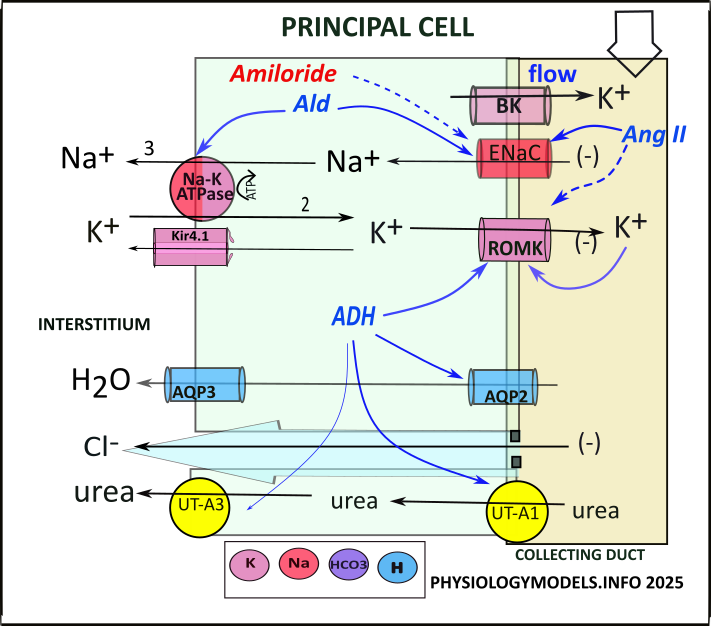

Principal Cell

The role of the principal cell is potassium secretion and water reabsorption. And, it is unique in that it initiates the urea cycle.

It is instructive to compare the transporters and channels in the principal cell to those in the DCT (the two illustrations are side-by-side in the Illustrations section below). Both have apical ENaC and ROMK channels plus basolateral sodium-potassium pumps and Kir channels. The difference is that in the principal cell BK channels replace NCC and ClC of the DCT. The DCT has no paracellular activity but both can activate aquaporin channels.

Water Reabsorption

Baseline activity in the principal cell (PC) involves the content-driven ENaC. It allows the diffusion of the filtrate sodium with chloride and water following paracellularly. The chloride movement is facilitated by the lumen-negative potential always associated with ENaC activity.

Potassium Secretion

Hyperkalemia leads to 'potassium wasting' in the DCT and the same occurs in principal cells though the mechanisms are different. Here, the 'wasted' filtrate potassium increases ( ) ROMK permeability adding potassium to that picked up passing through the DCT. The potassium efflux is also facilitated by the lumen-negative potential established by ENaC activity.

) ROMK permeability adding potassium to that picked up passing through the DCT. The potassium efflux is also facilitated by the lumen-negative potential established by ENaC activity.

BK (big potassium or maxi-K) channels are unique to PC. They permit additional potassium secretion under the 'stress' of high filtrate flow. This usually occurs during hyperkalemia because of decreased sodium chloride reabsorption in the DCT. And, the flow 'washes away' the secreted potassium maintaining the cell-to-filtrate potassium concentration gradient.

The sequence of events concerning potassium secretion are:

- Filtrate potassium increases ROMK activity.

- Increased filtrate flow increases potassium diffusion through BK channels.

- Increased flow maintains potassium concentration gradient.

During hypokalemia, ROMK channels are inhibited and BK channels are not activated. These responses reduce potassium secretion and mitigate hypokalemia.

Regulation

Reminiscent of DCT activity, in the presence of hypovolemia RAAS hormones favor water reabsorption over potassium secretion. Aldosterone stimulates ENaC and sodium-potassium pumps to increase sodium, and chloride, reabsorption. ADH inserts and activates apical AQP2 channels increasing osmosis.

As in the DCT, angiotensin II inhibits ROMK channels. This inhibition counters the stimulatory effects of hyperkalemia and ADH on ROMK.

Urea Cycle

Urea has not been reabsorbed along the nephron until the filtrate reaches the IMCD. A small amount always diffuses from the PC but urea does not normally make a significant contribution to the osmotic concentration. This changes when ADH trafficks UT-A1 channels to the apical border of the PC. ( ).

).

During hypovolemia urea accumulates in the interstitium. And, because constitutive UT channels in the Henle's loop and the vasa recta are not up-regulated to match the PC diffusion, the urea accumulates in the interstitium.

Urea is slowly removed from the interstitium by diffusing through UT-A2 channels into Henle's descending limb. This route allows the urea to be recycled to the principal cells to either bypass the UT-A1 channels or be recycled to the interstitium.

If urea diffuses into the vasa recta descending limb it will re-enter the systemic circulation and eventually by refiltered at the glomerulus.

On the average, approximately 50% of filtered urea ends up in the urine. And, "no", normal urine is not yellow due to urea. The color comes from urochrome, a waste product of hemoglobin degradation.

***************************

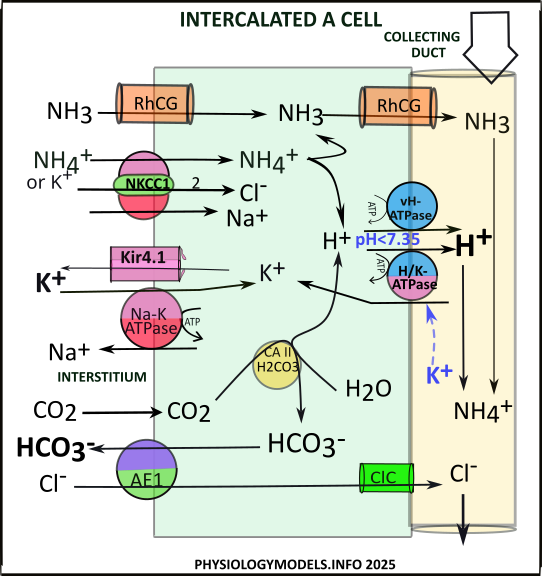

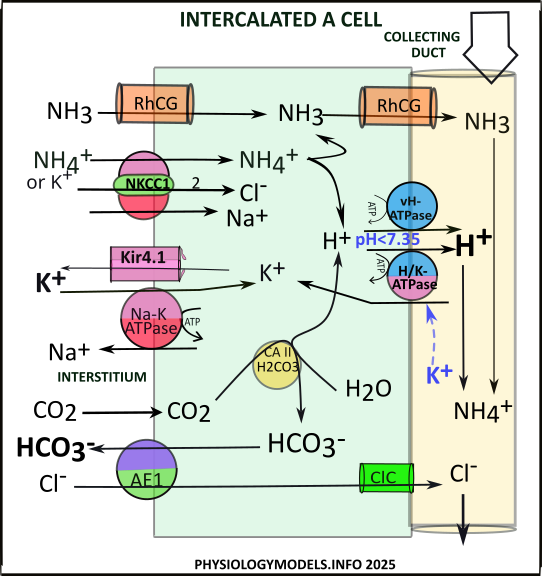

Intercalated A Cells (IC-A)

The role of the intercalated A cell is to mitigate acidosis.

During acidosis, ammoniagenesis in the PCT delivers ammonium downstream to TAL that transfers ammonia to the interstitium. There it buffers hydrogen forming ammonium. Both of these are taken into IC-A. The ammonium is transported along with sodium and chloride by NKCC1 while ammonia diffuses through RhCG channels.

At the average pH of 7.40, the ratio of ammonium to ammonia is 99:1. Ammonium is a very weak acid meaning it 'does not like to give up its hydrogen.' However, if free hydrogens are removed from the surroundings, it will then be 'encouraged' to provide a replacement.

In the cell, two pumps, vH-ATPase and H/K-ATPase, actively secrete hydrogen. This is the driving force that causes ammonium to become ammonia. The accumulating ammonia diffuses through RhCG channels into the filtrate. There, it buffers the afformentioned hydrogen to reform ammonium.

The reaction catalyzed by CAII also provides hydrogen for secretion. It converts interstitial carbon dioxide, from TAL activities, to bicarbonate and hydrogen. The hydrogen is secreted by either vH-ATPase of H/K-ATPase. The bicarbonate is transferred to the interstitium in exchange for chloride that diffuses to the filtrate.

The sequence of events is as follows:

- NKCC1 uptakes ammonium.

- Hydrogen from ammonium is secreted by vH-ATPase or H/K ATPase.

- Ammonia diffuses into the filtrate via RhCG channels.

- Hydrogen & ammonia recombine to form ammonium.

- CAII converts carbon dioxide to bicarbonate & hydrogen:

- ...Hydrogen is secreted by vH-ATPase or H/K-ATPase.

- ...Bicarbonate is reabsorbed by AE1 in exchange for chloride.

- Chloride diffuses to filtrate via ClC.

Potassium/Alkalosis Connection

If upstream activities in the DCT have 'wasted potassium', this filtrate potassium will inhibit ( ) H/K-ATPase activity. The result is reduced uptake of filtrate potassium along with reduced secretion of hydrogen. This is counterproductive to the job of 'mitigating acidosis'.

) H/K-ATPase activity. The result is reduced uptake of filtrate potassium along with reduced secretion of hydrogen. This is counterproductive to the job of 'mitigating acidosis'.

Regulation

Acidosis increases the secretion of hydrogen by stimulating vH-ATPase and H/K-ATPase activities. The increased secretion of hydrogen mitigates acidosis.

***************************

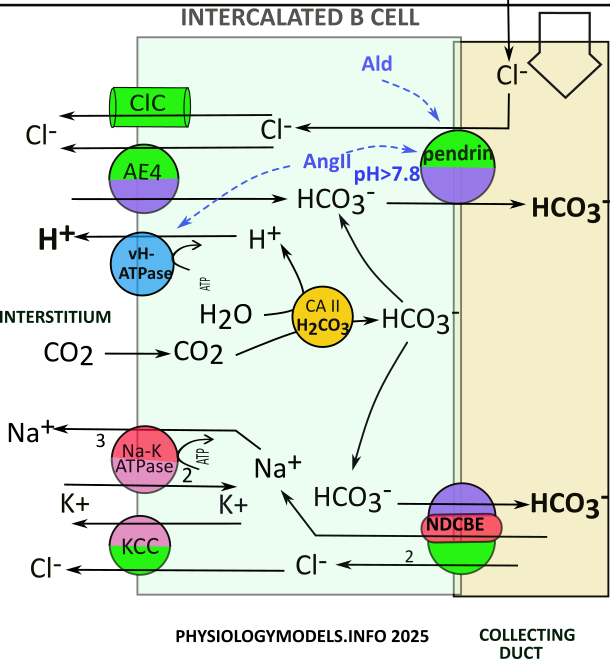

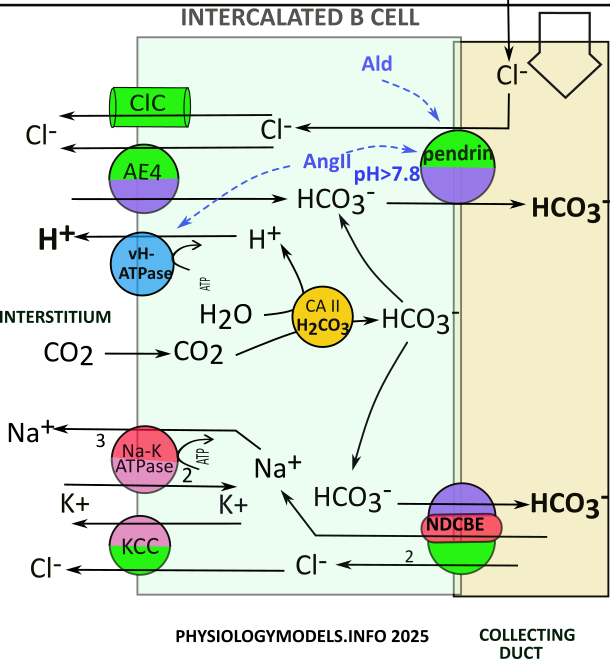

Intercalated B Cells (IC-B)

The role of the intercalated B cell is to mitigate alkalosis. It does this by secreting bicarbonate and retaining hydrogen.

The pendrin transporter is unique to these cells. It is apically located and secretes bicarbonate while reabsorbing filtrate chloride. The amount of chloride in the filtrate is the controlling factor in its activity. This being the case, chloride abundance must be linked to alkalosis.

In the PCT, alkalosis reduces ammoniagenesis and therefore filtrate ammonium. On reaching the TAL, less ammonium limits the overall reabsorption by NKCC2; this leaves chloride in the filtrate for pendrin activity.

Pendrin also requires bicarbonate; this comes from CAII activity. Interstitial carbon dioxide...from TAL activity...is converted to bicarbonate and hydrogen. Pendrin can now operate. The hydrogen is pumped to the intersititum by vH-ATPase. The chloride goes to the interstitium through ClC channels. It is also transported there, in exchange for more bicarbonate, by AE4.

The sequence of events is as follows:

- Chloride attaches to pendrin.

- Pendrin exchanges chloride for bicarbonate.

- Chloride diffuses to interstitium via ClCchannels.

- Chloride is exchanged for bicarbonate by AE4.

- CAII converts carbon dioxide to hydrogen & bicarbonate.

- Bicarbonate is secreted by pendrin or NDCBE.

- Hydrogen is pumped to interstitium by vH-ATPase.

- NDCBE uptakes sodium & chloride from the filtrate.

- Sodium is reabsorbed by the sodium-potassium pump.

- Chloride is cotransported with potassium by KCC.

Regulation

During hypovolemia aldosterone & angiotensin II stimulate ( ) pendrin trafficking and activity . The effect is to increase chloride reabsorption with sodium increase from nearby principal cells. The effect is to increase the interstitial osmotic concentration. This increases water reabsorption that mitigates hypovolemia.

) pendrin trafficking and activity . The effect is to increase chloride reabsorption with sodium increase from nearby principal cells. The effect is to increase the interstitial osmotic concentration. This increases water reabsorption that mitigates hypovolemia.

***************************

Illustrations

***************************

Diuretics

Diuretics inhibit solute reabsorption thus reducing the osmotic concentration that facilitates osmosis. These drugs are often classified as 'potassium-wasting' or 'potassium-sparing'.

The' loop' diuretic furosemide inhibits NKCC2 in TAL. Solute reabsorption in this nephron segment accounts for approximately 60% of the osmotic potential in the medullary interstitium. Reduction of this much solute reabsorption provides significant diuresis. However, a side-effect is increased sodium delivery to ENaC channels in downstream DCT and principal cells.

Increased sodium delivery also occurs with thiazide that inhibits NCC transporters in the DCT. By blocking sodium and chloride uptake by these transporters, the medullary osmotic concentration is reduced, but less so than by inhibiting TAL activity. Again, the increased abundance of sodium in the filtrate causes 'potassium wasting'.

The potassium-sparing diuretic amiloride inhibits ENaC channels found in the DCT and principal cells. This inhibition counters the sodium wasting caused by the 'loop diuretics' thiazide and furosemide. Accordingly, amiloride is usually administered with either of the other two.

The final question is ... "Why do I have to urinate so much after drinking alcohol ?" The answer is: The number of aquaporin channels throughout the nephron is maintained by ADH. If the base-line ADH level drops so will the number of aquaporin channels and water will be lost in the urine.